Portrait

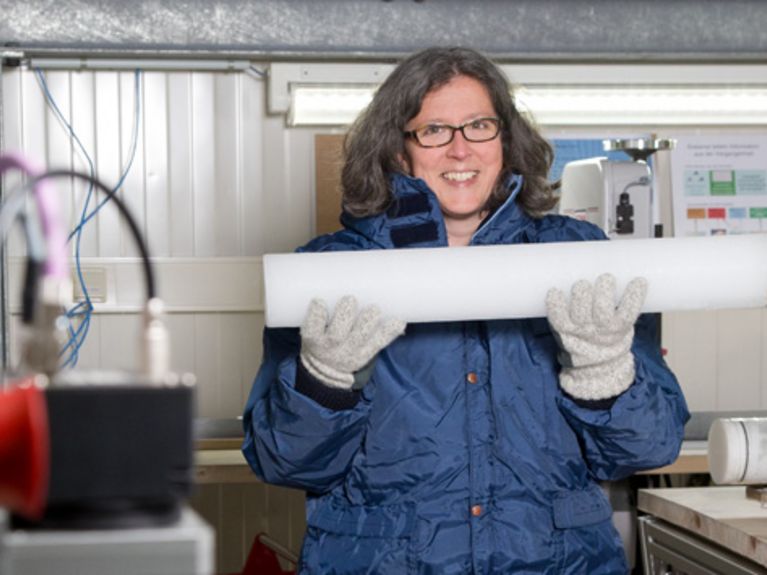

The ice expert

Photo: Martina Buchholz

Angelika Humbert coaxes secrets from the cold element. For this purpose, she conducts her research in the Antarctic, in Greenland and in Bremerhaven. The glaciologist wants to find out what the climate was like in past eras, and what it will look like in the future.

Typically, a person becomes a polar research scientist because he/she has read, as an adolescent, a book about Amundsen’s expedition to the South Pole. Or because the geography teacher told fascinating stories about the Arctic. Perhaps there were unforgettable memories of a childhood by the sea. But this was not the case for Angelika Humbert: she discovered polar research while taking care of her baby at home in Darmstadt.

“I was in my mid-twenties, had completed my diploma in physics and my son had just been born,” reports the now 45-year-old scientist. She decided to take time out in order to look after her child. In those four years the trained nuclear physicist read up on the science of the cold substance. A seminar on fluid mechanics at the end of her study programme at Darmstadt Technical University got her on track. At that time, between feeding and changing nappies, the young physicist began thinking about why it is that glaciers actually flow and what precisely occurs when icebergs calve: “During my maternity leave, it became clear to me that a change to the field of glaciology was what I wanted.” And that is what she did. After sojourns in Münster and Hamburg, Angelika Humbert came to the Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI) in Bremerhaven three years ago. She is there from Mondays to Fridays and spends the weekends with her family in Darmstadt. At AWI the physicist leads the Department of Glaciology – as the science of ice is called in technical jargon. The position is combined with a professorship at the University of Bremen.

Her research results make headlines worldwide from time to time. Thus it was when Angelika Humbert announced a record decline in the ice sheets of Greenland and the Antarctic last summer. Jointly with colleagues at AWI, she assessed satellite data and determined that the two ice shields together lose about 500 cubic kilometres of ice per year. “That corresponds to an ice sheet that measures about 600 metres in thickness and would be able to cover the entire metropolitan area of Hamburg,” says the glaciologist. That such findings are politically relevant is not shocking to her – quite the contrary: “It is our assignment to provide data that enable the politicians to take appropriate action.” But the arguments still have to be scientifically correct: “It is frequently said that all ice sheets are melting away, but that is false,” says the glaciologist. “Only the Greenland ice shield is melting on the surface, while in large sections of the Antarctic there is however no such thaw.” It is primarily the glaciers there that are rapidly shrinking.

What kind of individual consequences this will bring and what will subsequently happen to the climate, Angelika Humbert is investigating with her team. “I can combine my paper-and-pencil theories wonderfully with concrete observations here,” she says. Research scientists in Bremerhaven are reconstructing, for example, the climate of bygone eras from ice cores that are collected from boreholes in Greenland or the Antarctic. They measure the thickness of ice shields using radar methodology. Satellite data provide them with images of the surface, and mathematical modelling enables prognoses for future development.

Expeditions to the Polar Regions provide the necessary practical orientation. Angelika Humbert is already looking forward to her next big field campaigns. The first one will beckon her to the Antarctic from November to January. The second trip in the summer of 2016 is planned for the Greenland ice shield: there new drilling programmes are meant to expand our knowledge of the interaction between ice and ocean.

Neither in the field campaigns nor at the Institute in Bremerahven is Angelika Humbert alone among men: particularly in the field of glaciology, there is a surprising number of women – even in management positions. “In the meantime, men are also taking time off for paternity leave,” Humbert has observed. Combining family and career is, fortunately, no longer only a topic for women.

For her part, she is supported by her men at home: “For my career, right from the beginning there was always 100% support,” says Angelika Humbert. Her husband, likewise a physicist and her now 19-year-old son manage the everyday routine – on the weekend the family is together again. Cherished rituals are cultivated then: the big shopping trip to the organic farmers nearby or the extended Sunday breakfast with discussions about everything under the sun.

Week after week the scientist commutes by train between Bremerhaven and Darmstadt, a trip of at least 5 hours each way. What most people would call an imposition, she considers a blessing: “I couldn’t imagine a better life than this.”

Readers comments