Portrait

From Garching to Hawaii

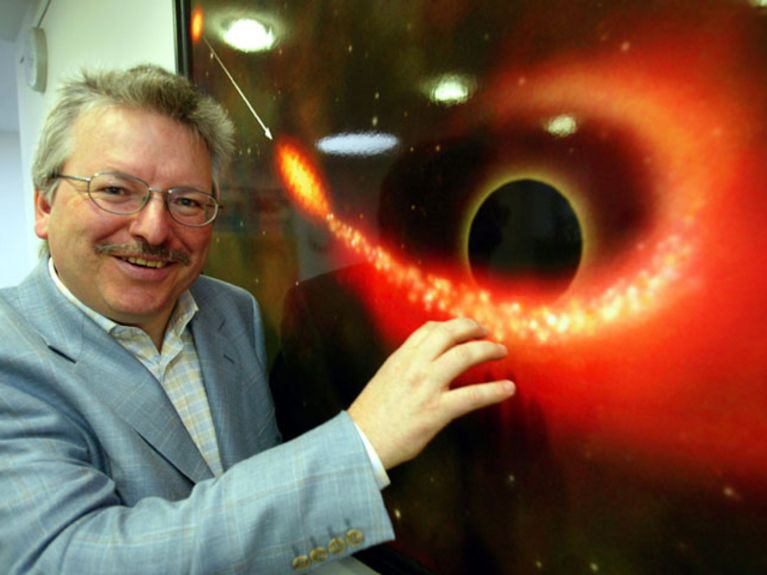

Prof. Günther Hasinger. Image: ESA

Günther Hasinger is the director of science at the European Space Agency (ESA). His love of astronomy got its start at the observatory in Munich - and has taken him around the world.

Last October, Günther Hasinger took a trip to South America and visited the small city of Kourou in French Guiana, where the European Space Agency (ESA) has its launch site. Moments like those he experienced in Kourou make him very happy. Hasinger was smiling from ear to ear as he and his colleagues stood in the sweltering heat. He could hardly wait for the moment to arrive—the launch of the BepiColombo mission.

Just the force of the sound waves on his lungs was overwhelming, Hasinger says: “Everything around us shook, even though we were ten kilometers away.” But he recalls that the thought of where the probe was heading was even more mind blowing. BepiColombo was on its way to Mercury, the planet with the shortest orbit around the Sun in the Solar System. The trip will take seven years, and the satellite needs to cover nine billion kilometers during this time. BepiColombo is propelled by power from solar sails, which Hasinger says is nothing less than sensational.

Hasinger is 65 and has been director of science at ESA since the end of 2017. He coordinates research projects for 500 employees from the space center just outside Madrid. Over 20 missions are currently in the active phase, including Europe’s first Mars probe, the XMM-Newton X-ray observatory, and the Gaia probe, which aims to obtain precise measurements on nearly two billion stars as it travels through space.

In 2017, researchers on Hasinger’s team at the Institute for Astronomy at the University of Hawaii discovered a cigar-shaped celestial object. They dubbed it Oumuamua, which is Hawaiian for “first visitor” or “messenger.” The object’s bizarre shape fueled speculation on its origins. Image: ESA

“Snacks” for black holes

Hasinger’s specialty field is X-ray astronomy. Over the course of his career, he helped to build countless X-ray satellites and analyzed the data they provided—or, as he puts it: “My greatest achievement was that I used those satellites to take a long, long look at any empty spots that were out there in space and discovered thousands of black holes in the process.” Hasinger was appointed director of the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam in the mid-1990s before subsequently moving on to the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics in Garching and then the Institute for Plasma Physics.

He became head of the Institute of Astronomy at the University of Hawaii in 2011. His colleagues there discovered a bizarre cigar-shaped object in space measuring around 400 meters, which they dubbed “Oumuamua.” Oumuamua soon became the subject of media reports around the world, but no one is certain exactly what it is even today. Hasinger thinks Oumuamua is a comet made of solid rock, and he grins when asked whether it could also be an alien spaceship. “I don’t think there’s anything wrong with a bit of speculation,” he says. The only time he loses his patience is when he meets people who seriously maintain that the world is a disc. Unfortunately, the number of those who refuse to believe otherwise is increasing these days: “There’s no getting through to these people with reason and solid arguments. It makes you want to pull your hair out.”

Hasinger says that one of his most important tasks is to share his enthusiasm for space. In other words, he wants to get others excited about the cosmos, or at least give them an idea of how important basic research is. This is why he often uses vivid imagery in his lectures. He tells his audience that BepiColombo will be subjected to temperatures as hot as those “in a pizza oven” on Mercury and that the Gaia space probe is essentially ESA’s “workhorse.” And he came up with a witty metaphor to illustrate how “hungry” black holes can be: “Some of them devour an entire mountain every day—as easily as a snack.” Hasinger can’t help but chuckle himself when he uses these images.

He says he has always loved being in the lamplight to a certain extent. He grew up in Oberammergau, the small town in Upper Bavaria whose residents turn into amateur actors every ten years as they perform the story of Jesus’ final days in the Passion Play at the town’s open-air theater. At the age of just six, he was playing an extra and cheering Jesus on as he rode into Jerusalem on his donkey. Later in the play, he loudly shouted “Crucify him, crucify him” in the court of Pontius Pilate.

Hasinger played in a rock band as a secondary school student. The band was one of the hottest in greater Munich at the time.

As a student in secondary school, Hasinger played in a rock band. The group of five young, long-haired men called themselves “Saffran” (“Saffron”) and played experimental krautrock with Hasinger on bass and occasionally on the transverse flute. Saffran was one of the three or four hottest bands around Munich at the time and was even covered in Bravo magazine.

Hasinger had always been a tech enthusiast, so he got to solder any broken cables and replace the tubes in the amps for Saffran. When the band recorded its first album, he spent so much time in the studio that he completely forgot to apply to university. At some point his mother called because she was worried about losing her child benefit. “So I finally went to the university, and the only subject I could start immediately with my high school grades was physics.”

Cosmology came first, despite Hasinger’s love of music

During the semester break, he did an internship at the observatory in Munich. Since all of his colleagues there were on vacation at the time, he was the only one present to witness the Nova Cygni’s unusual birth in 1978. That was the moment his love of astronomy began. He fiddled with the spectrograph and improved the view step by step so he could still observe traces of the nova in the heavens weeks later. And he continued to do so until Oktoberfest eventually began and the lights from the rides and stalls obscured the skies. From then on, Hasinger couldn’t imagine his life without space.

Does his continued enthusiasm get on some people’s nerves these days—for example, his wife’s? “We’ve settled into a healthy routine over the years,” Hasinger says. Which is to say, he tries not to think about space too much when he’s at home. Instead, he and his wife frequent museums; they have an annual membership in Madrid so they can explore a different exhibition every weekend. Their favorite is the Museo del Prado, the famous art museum known for its works by the Spanish masters.

Hasinger is still in touch with his old bandmates from Saffran. One of them became a jazz musician and tours the clubs, while another played for Roy Black for many years before working as a solo entertainer on a cruise ship. Hasinger says he loved music but that he probably loved the planets, satellites, and his research just a little bit more. At the end of this year, he wants to travel to Kourou in French Guiana again after completing his activities as an expert assessor at Helmholtz. That’s when the next ESA satellite, Cheops, is scheduled to be launched into space.

The liftoff has been set for December 17. The Ministerial Council will be determining a new budget for ESA shortly prior to that in Seville. Hasinger notes that ESA’s Science Faculty has unfortunately been “stuck in the shadows” to some extent over the last 15 years because other topics have typically been at the forefront of public discourse. The Science Faculty at ESA is allotted 530 million euros per year, around a tenth of the total budget. Hasinger wants to increase this figure.

There are still so many secrets out there, he says. One that he definitely wants to see revealed as soon as possible is whether the theory that black holes are actually dark matter is true. “We don’t know much about either one, and getting to the bottom of this would be killing two birds with one stone.” He would love to witness this discovery before the end of his career.

Hasinger and his wife want to make Berlin their main residence in the near future. One of their two sons lives there and is a bioengineer who researches early diagnosis methods for prostate cancer at a start-up. Their granddaughter is four and a half, and Hasinger says he has already succeeded in getting her a bit interested in space. “Her latest question is why we need the stars at night when we can just turn on the lights.”

The Strategic Evaluation of the Research Field and their Research Programs

Between September 2019 and February 2020 , Helmholtz's research was evaluated by high-ranking international experts. The strategic evaluation aims to review the strategic plans of the research field and to propose a basis for the distribution of funding among the programs. Günther Hasinger was chair of the high-caliber panel of international recognized experts.

The Strategic Evaluation of the Research Field and their Research Programs

Readers comments